FRANCES' LIFE CYCLE

In 2004, Frances was the fourth hurricane in what turned out to be a very active season. Not only did Frances damage

portions of Florida and the U.S. East Coast, but the Bahamas took the brunt of the storm, as well. As you will see, storms

like Frances don't just wander aimlessly across the Atlantic to places like the U.S. and the Bahamas. Instead, there are

steering mechanisms that force them to move where they do.

On August 21, a strong tropical wave emerged off the coast of Africa in what soon became Frances. Storms such as these

are often called Cape Verde type storms. By late on August 24, a tropical depression formed from this disturbance. The

very next day this depression turned into Tropical Storm Frances, approximately 1,400 miles east of the Lesser Antilles. On

August 26, this storm rapidly intensified into Hurricane Frances. Over the next week, Frances moved steadily west-northwest

toward Florida, as the image below clearly shows, fluctuating between Category 2 and Category 4 strength.

On September 2, Frances made its first landfall in the central Bahamas, as a Category 3 storm with 120 mph winds; however,

due to weak steering currents, the storm didn't strike Florida until late on September 4, at Category 2 strength. Even though

Frances weakened a little by landfall, it still directly caused seven deaths with damage estimates near $9 billion.

This is an image of Hurricane Frances' track as if moved across the Atlantic. Also, it shows its fluctuations in intensity,

courtesy of Weather Underground.

What causes most tropical systems in the Atlantic to move in a

clockwise circulation, like Frances did? The answer lies

with

subtropical areas of high pressure which provide the steering currents

for hurricanes to move. This current lies in a layer

between the lower and upper troposphere, or from 850 mb to 200 mb. Generally speaking, most meteorologists look at the

mid-tropospheric level at 500 mb for the mean steering current.

The flow at this level often varies, meaning that a hurricane

can move slow and erratically or at a quick pace over 20 mph.

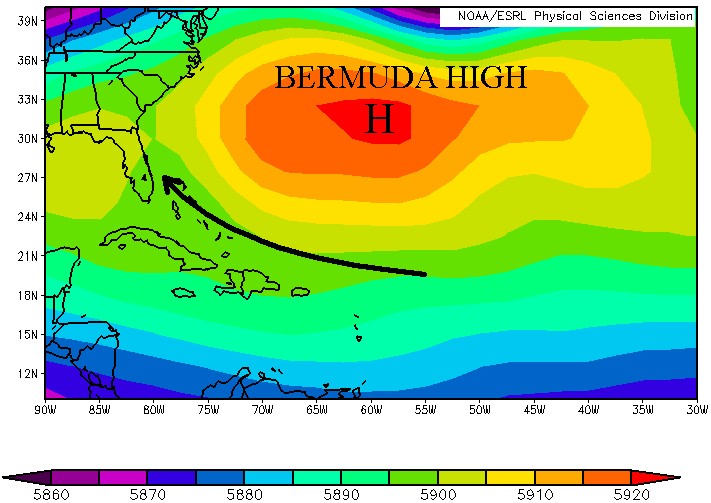

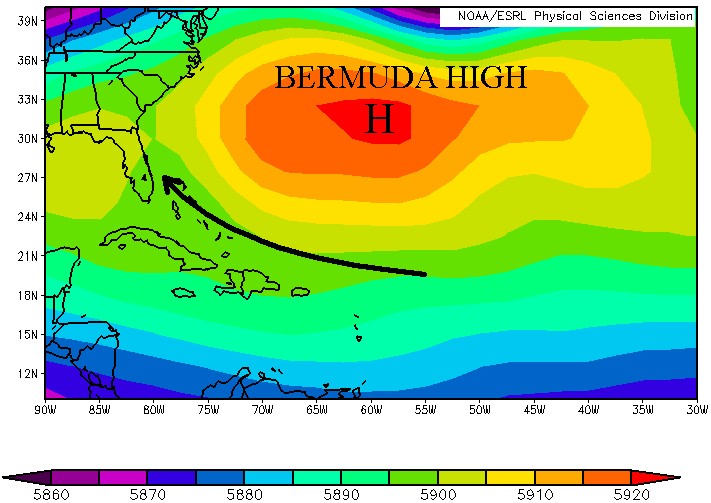

In the case of Hurricane Frances, the Bermuda High was largely responsible for its track. When the disturbance that became

Frances moved off the coast of Africa, it was steered to the west along

the southern flank of the Bermuda High. As the storm moved

further to the west, it got caught up in the clockwise flow around the

high and started to move more toward the northwest,

as the 500 mb heights image below shows. This image of 500 mb wind vectors from the week Frances moved across the Atlantic

also shows the flow around the Bermuda High that steered the storm into Florida.

This is an image of 500 mb heights from August 26 to September 4, the week Frances

moved across the Atlantic. It shows the Bermuda

High that steered

Frances

toward Florida, as well as, Frances' track as it turned more to the northwest around the high, courtesy of ESRL.

PAGE 1 2 3 4 5 6